Your Parents Are Old

And then, suddenly, so are you

If you like this piece, please push the LIKE/HEART button because it helps other people find the piece which helps me gain new subscribers 🫶

—

Last week, at 3 am on a Wednesday, my mom and stepdad landed in Durham, North Carolina, where I live. And so I got them an Airbnb.

“Oh this was so nice of you, Alexander,” my mother said, ignoring the shared understanding that I was using money to avoid feeling burdened.

“You should’ve let her stay with you,” said my friend Greg. “That would’ve been the right thing to do.”

But during the workweek, I am snippy and regimented. I use the guest room for meditation, the living room for client calls, and the rest of the house for more silence.

And silence is not a word my mother has ever known.

To be clear, my mother is not more of a burden than most mothers. She and Jonathan aren’t even here to visit me, but instead, to buy a small home in an active retirement community in South Carolina (median price $480k) because they can’t afford one back home in San Diego (median price $1m+), and “I’m 74,” Jonathan said, “if I’m going to take advantage of all of the amenities at one of these communities, I’ve gotta shit or get off the pot.”

I think about what those amenities might be.

Karaoke or trivia. Maybe golf. But he golfs only once a year so it doesn’t add up. Maybe they’re swingers.

They’ll never actually leave San Diego, though.

They’ve lived in California for 34 years, they love hiking and mountains and beaches, and by the time you get to your 70s, it’s too difficult to ditch your friends and your dentist and your favorite UPS store or the familiar vibration you notice in your hands as you clutch the steering wheel and drive down the I-5 for the 22,352nd time. All the mundane scaffolding of life that keeps you feeling safe.

“Could you actually give up Porkyland?” I ask my mother, referring to the Mexican restaurant she’s walked to every day for the past five years.

“I know, Alexander,” she begins, “but I promised Jonathan that I’d at least look at a few of the communities, and so, here we are.”

We walk the four blocks to my house from the Airbnb. We grab lunch and go for a hike. They’re fast for their age. Jonathan still runs 5Ks. My mom walks 2-3 miles a day.

But, after the hike, when we’re sitting at my place, and it’s time for them to head back to their Airbnb, they have no idea where to go.

I text them the address. They both pull up Google Maps and hit start.

“Head West,” my mother’s phone says.

“Head West,” Jonathan’s follows.

“Oh god,” I say, remembering that this is a thing they do. “You don’t need her on both phones.”

“We do though,” Jonathan says, standing up from the couch.

My mother studies her screen as she starts toward the door, searching for clues of West. “Sometimes we think we’re losing our minds,” she begins, “but then we remember we’ve always been like this.”

I’m not so sure.

Sand.

That’s how the mind slips. Slowly, off your palm, grain by grain, and by the time you think to close your hand, you’ve forgotten how.

I imagine my mother and Jonathan have both seen the signs.

And when they tell me they’re looking for an active community with clubs and pilates and trails to walk on, what I really think they mean to say is that they don’t want to have to bear witness to those signs alone.

If we lived in another country, this would all fall on me to figure out.

Mexico, Colombia, Costa Rica, Greece or Spain. Places where the cohabitation rate of elders living with their adult kids sits consistently above 50% as opposed to the U.S., where it sits around 10-12%.

I think about what it would be like for my mother to move in with Ben and me.

She speaks more often than I, which is very hard to do, and so, I’d be stuck, every evening, listening to her tell me about all the neighbors. About how Brett and Allison down the street seem to be having marital issues.

“Who?” I’d ask.

“Oh, you haven’t met them,” she’d say, “but you will. And when you do, you’ll see how he doesn’t even look at her when they talk,” she’d pause without pausing, “reminds me of your friend Kyle’s parents who you made us have dinner with when we visited freshman year.”

“I don’t remember—,” I’d say.

“—I give them six months.”

I could deal with this for one night, maybe two. But it’d soon take its toll, and then she’d feel like she was invading my rhythm, I’d feel guilty for making her feel that way, and then she and Jonathan would head to one of the communities they should’ve gone to from the start.

It’s all very hard, though, because neither living with me nor living at an active retirement community is that good of an option for her.

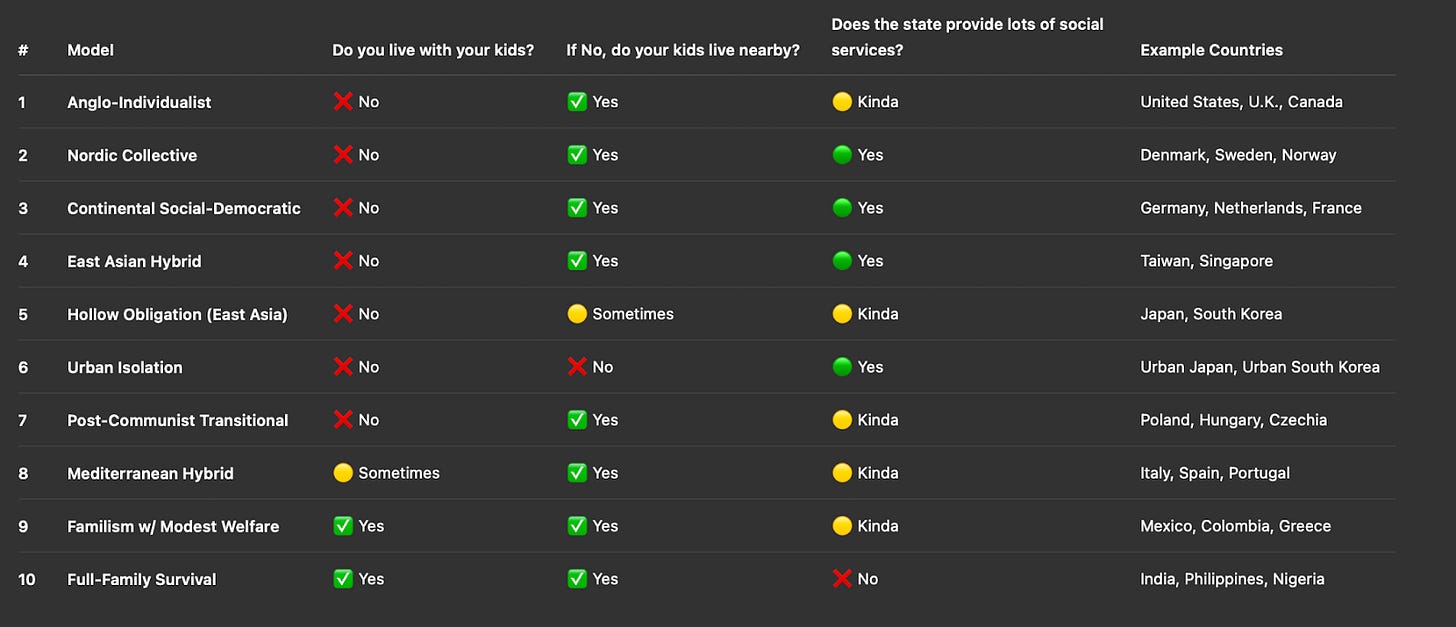

And as far as options go, there seem to be 10 or so ways that one can grow old in modern society, all of which circle around three main questions:

Do you live with your kids? (Yes/No)

If No, do your kids at least live nearby? (Yes/No)

Does the state provide lots of social services? (Yes/No)

The American model looks like No/Yes/Kinda, where most old people live in a prison with other old people, 80% of American elders are within 100 miles of their kids, and the state provides minimal Medicare w/Assisted Living Waiver programs.

An oversimplification of the elder-oriented world via ChatGPT looks like this:

You’ll notice that no rows are all green, but that red isn’t necessarily bad.

For example, “Do you live with your kids?”, “No”, should probably be green because people don’t want to live with their adult kids, and doing so seems to only be a thing you do if society tells you that you must, or if you’re poor.

The data comes from OECD reports, the World Happiness Report, UN datasets, a few country-specific aging studies, and some GPT inference, which means it’s far from perfect. But the point isn’t that people magically become happier when old people stop living with their kids; it’s that the countries where people are happy and wealthy also happen to be the places where old people choose not to live with their kids.

I look at the last row in the table.

Specifically India, where the cohabitation rate reaches 80%, and I think about how difficult that must be because Indians, just like my mother and me, are very loud.

And then I wonder if my mother would be louder if she were Indian.

It seems impossible, but since there are 1.44 billion Indians, specifically 18.5 million women between the ages of 71-75, that leaves us with roughly 3.7 million 71-year-old Indian women, and it is quite unlikely that my mother is louder than all 3.7 million of them.

Still, I am not convinced.

Her favorite thing to do is to talk to everyone about nothing, and 90% of the time when I call her, she is standing in a parking lot telling me that she has to go because she’s talking to a new stranger.

“Her name is Angie,” she’ll say to me while looking at the woman in front of her, “and she goes to the same Mormon church as the Wades,” a family who lived on the same street as us, whom we haven’t spoken to in 15 years.

“Does Angie know the Wades?” I’ll ask.

“She does not,” my mother will say, “but she thinks she has heard of them,” and then my mother will hang up on me, returning to Angie until Angie’s ears fall off or until another stranger stumbles into my mother’s path, and that type of mother, as well as most mothers, would certainly not be happy living trapped without strangers to talk at in an ADU above my garage.

–

It’s evening now.

Day four of her South Carolina Retirement Community Tour.

I call to find out how it’s been going.

“Well, we just saw our third community and…it was okay,” she begins. As I expected. “Jonathan seems to like it, which is great, until he dies and I’m stuck here alone.”

“Yeah,” I said, “but, by then, you’ll have a bunch of nice old women you can gossip with and they’ll all be your friends or community or whatever, you know?”

“But Alexander,” she said into the phone, her voice a bit softer, “I don’t want these women to be my community.”

“Well that’s not really how this works,” I wanted to say, but did not.

Because once you reach a certain age, you become sort of stuck with whoever is around.

Like Jonathan’s mom, Eve.

She was 107 when she passed away in an assisted living center.

Who would she have said were her community? The other residents or nurses who turned over year after year? The son and granddaughter she saw once a month? My mother?

“We had a lovely conversation,” my mother would have said to the nurse after spending five hours in a conversation with Eve.

“Ma’am,” the nurse would’ve said, leaning in to place her hand atop my mother’s, “Eve’s been dead for hours.”

And so the question remains.

What should my mom and Jonathan do? What, as a society, should we do with all the old people? How do we keep them healthy for a long time, while also making sure they’re joyful and busy and filled with meaning, without forcing them to find purpose through the caretaking of grandkids that an increasing number of them are never going to have, and how do we do all of this without bankrupting the economy + overburdening the medical system and has anyone anywhere figured this out?

Yes.

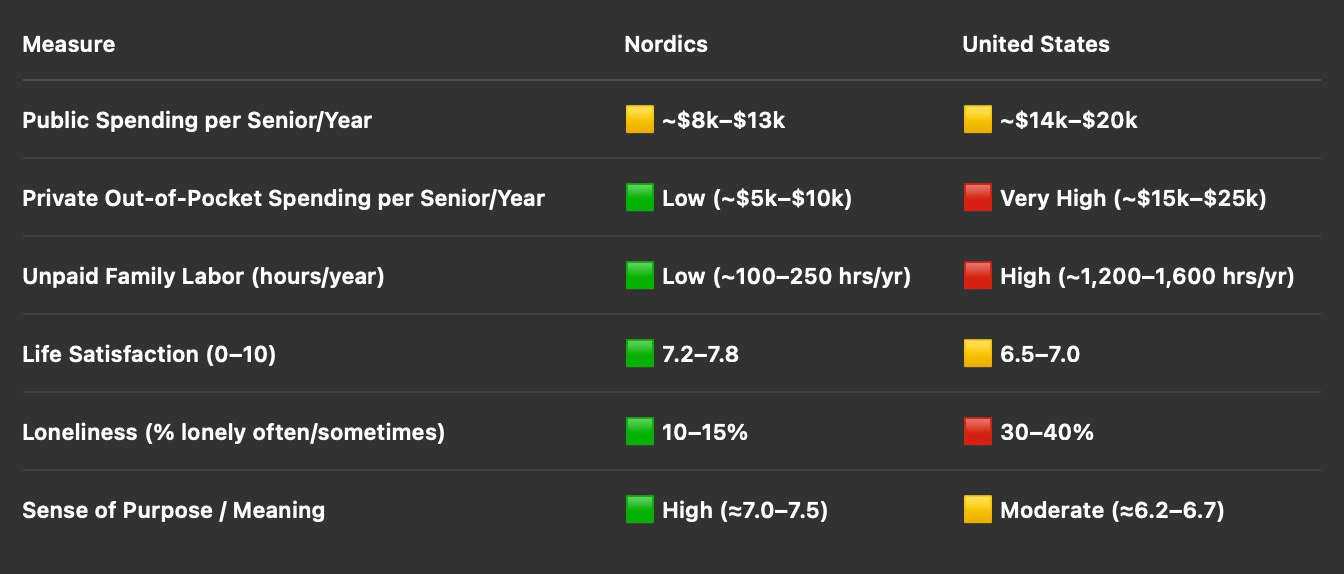

Denmark/Sweden/Finland/Norway. Obviously.

The Nords have a model that I think most Americans would hate, but basically, once you reach a certain age, you get universal basic income + social services that everyone has to accept wherein, every six months or so, a social worker shows up to your house to enroll you in mandatory benefits like home cleaning, bathing, grocery, meal prep, and transportation to social events and all of this is not optional because by making the assistance mandatory, it removes the shame around feeling incapable or poor while helping solve the ultimate goal of keeping elder happiness high while preventing the state from paying for expensive crisis hospitalizations.

GPT alleges that the math seems to work too.

My mom would probably hate this.

So would Jonathan.

So would many of you.

Because a system like this comes with high taxes and high government spending, and we seem to do both of those things quite poorly here.

People always cite the DMV.

The Danish DMV is nice though. They have digital driver’s licenses.

But this is neither here nor there because systemically changing America is too hard and my mom isn’t moving to Denmark because the weather is bad, her stories wouldn’t land, and going back to what I said earlier, old people don’t move.

“Wait, are you serious?” I say to her on the tail end of her trip as she sits down at the dinner table with Ben and me.

“Yes,” she says, telling us about the fifth community they saw. “We’re so excited,” she continues. “We picked the model of the house they’ll be building for us. We even stayed in a similar unit for three nights, and LOVED it.”

“Wow,” I say with a tightness in my gut. I force a smile. “That’s…great.”

“Yes!” she says. “We move in June.”

June? I think to myself. That’s very soon. Who’s going to decide everything? What if something goes wrong? Is this poor, rash decision-making an example of her starting to lose her mind?

“That’s so great,” Ben said.

Does Ben also not get it?

Does he not understand that, since Jonathan is older than her, and a guy, that she’ll most likely end up stuck there for 5-10 years…alone? And then what?

“Alexander, everyone was so happy there,” my mother continues, “We spoke to so many people and they all had such great things to say.” She ruffles through papers and brochures, readying to walk me through the home they’re picking. Fixtures. The larger showerhead. How they’re doing Whirlpool instead of KitchenAid. Why she wants her office to be on the left side of the garage and not the right.

Our dog, Ralph, walks up.

“Oh! And we asked for a see-through door so that when Ralph comes he can sit and look out the front! He’ll love that. Won’t you, Ralph? Good boy,” she says scratching his little head.

I pause to try and relax my stomach. And then I notice an excitement in her. One that I haven’t seen in a while. Maybe it’s adventure.

Or hope.

Because she is seventy-one. And still going. Still deciding and planning. Still doing improv classes and tutoring the neighbor’s kids.

And so perhaps I should notice more often.

How she lights up when she sees her cousin’s baby, offering herself up as babysitter as often as possible, to relish in whatever grandmother-ness she can, because deep down she knows that just because she wants something doesn’t mean it’ll arrive in time.

And I should listen better.

To the change from four years ago’s, “One day, Jonathan and I will go hiking in Argentina,” to last month’s, “Oh, Argentina…” she said, “that sounds so nice.”

Because today, though her mind is still fast and cutting, and there is so much she still wants to do, she has not the strength nor the money nor the time — sand slipping faster than either of us realizes, where she’ll probably never again rock climb or ice skate or travel too far alone. The voice in her head, the one she’s too careful to say aloud, now whispers, “Not in this life.”

And I don’t want that for her.

I want her to go to every place she’s ever read about in Reader’s Digest or Costco Magazine. I want her to see every beach and every mountain and know grandchildren she’ll probably never have and talk to every stranger in every parking lot because one day, so much sooner than I know, this will all go away and I’ll give anything to be Angie, standing in a parking lot being talked at by the loudest person the world has ever known.

And on the list of things she wants and still has enough time to do there are so many and yet so few and if “starting over in a new city,” is one of those things I hope she does it fully and I hope she does it now.

I still don’t know what we should do.

About all the people out there who are so much less fortunate than my mother.

About what we tax/mandate/subsidize, and what we don’t.

I believe our current system is broken, we don’t do enough to support the elder middle class, and I don’t have enough faith in either current political party to think we ever effectively will.

Fifteen years from now, when my mother’s mind starts to slip and she wanders out of her community in South Carolina and gets picked up by a helpful minivan family who wonders how this elderly woman is unable to tell them where she was coming/going but will easily tell them about how her late sister Diane’s ex-boyfriend’s father used to have a similar minivan that he bought from a man who had to sell it to pay for his wife’s rehab because she was a terrible alcoholic — a much longer story — but the van had great lumbar support, and then she asks the family how the lumbar support is and the dad says that it’s actually not that bad but sometimes, on longer trips his back hurts and so my mother calls her friend whose son is a chiropractor and three hours of this will go by until this kind family realizes that they’ve been kidnapped.

But in that moment, I’d love to feel good about what happens next — would love to know that she’s kidnapped a group of people, or even just a specific someone, whose job it is to actually look out for her.

Someone responsible for her well-being.

Someone I don’t have to pay.

Someone who brings her home.

If you liked reading this, please push the LIKE/HEART button at the top, because it helps other people find the piece which helps me gain new subscribers 🫶

Thanks guys

Questions from you, my lovely readers (please answer in the comments by clicking here):

If you are 50 years or older:

How would you rate your community that you’re not related to? (1 - 10, 10 being I have a crapton of friends)

If you currently have kids, do you want to live with them? If you currently don’t have kids, are you scared about not having someone to watch over you as you age?

If you are younger than 50:

Do you want your parents to, one day, live with you? Be honest.

When you imagine your own old age, what do you hope exists that doesn’t today?

I’m 68, retired 2 years ago. I went on two awesome trip and then my mothers health deteriorated and I came to stay with her.

I worked my tail off for many years and neglected my mother and my kids. Hospitals are 24/7 and I’ve always been the first to offer to work holidays.

I never would have thought I’d want to live like this, but surprisingly I love it. I love getting to know her again, learning things I never knew about her. It’s been the greatest gift I never knew I wanted.

Your mother is lucky to have you as a son and friend. It is obvious that you truly care about her and want the best for her. Getting older with grace, joie de vivre, a sense of adventure, curiosity, and a quick wit are just a few of the traits that your mom seems to embrace. Moreover, she definitely has a tremendous amount of love for you, Jonathan and her daughter! Great moving and honest piece, Alexander.... Love, MOM